Monday, 30 December 2019

Rationale - Index

Idea

In an ironic and somewhat darkly humorous twist of fate the inventor of the safety pin, Walter Hunt, died at the age of 63 from gangrene caused by a pinprick. A fact that is certain to make anyone scoff at the irony, it was the perfect idea for a poster.

Semiotics

In terms of Pierce's semiotics, this is categorised as an index. This is because what is visually communicated does not directly show the object in question but does, however, have a connection to the research as well as communicate the direct consequences of a safety pin. If a safety pin is the object and a pinprick is the cause then a plaster represents the connection. One of the earliest examples of an index that Pierce gave is the relationship between a murderer and his victim. This is a perfect example, as here the relationship between Hunt's death and what killed him is visually communicated.

Visual Communication / Design Principles

Photography is used to visually show the plasters, arranged as if in a hurry - desperate and in pain. The contrast between light and dark is high; creating drama and a sense of panic. The dark, blank background suggests nothingness - a cold and empty space. Furthermore, two images have been layered on top of one another to indicate a person's hands being outstretched in disbelief or at the realisation of death. The opacity has been lowered so that parts of the fingers are blurred and transparent to visually communicate hallucinations and temporary insanity - symptoms of severe gangrene. The image was further developed through the use of collage. Subtly, parts of the image are distorted or simply removed - to portray the lack of sanity and finally death.

Links to Research

In today's society with modern medicine, we would simply treat a pinprick with a plaster, however, in 1859 at the time of Hunt's death there was not the same knowledge as today, causing him to get gangrene - a serious and painful condition. The image visually communicating Hunt's death via plaster in such a dramatic way gives a subtle nod to the irony of his death - such a simple solution, that just wasn't available at the time.

Index Development

I had already established an idea for my 'Index' poster based on my research - which was to visually communicate the darkly humorous irony of safety pin inventor Walter Hunt's death via pinprick. I thought that this idea was suitable for this poster because an index shows evidence of the object, a cause and connection situation. My aim was to convey the direct consequences of a safety pin, and I thought that the best way to show this visually was through the use of a plaster. I initially thought about using fake blood and trying to capture the idea more directly, however, plasters have more of an indirect connection to injury - especially something benign like a pin prick.

I tried taking some fabric plasters and manipulating them using the scanner, however, the results of this were disappointing. The imagery was not strong and lacked anything interesting. I knew that instead of simply using the plaster imagery I wanted to communicate more that linked back to my initial research like pain, death etc. and this was hard to do with the flat, static images being produced on the scanner. I decided to take some photos with the plasters as I would be able to direct and control this more easily. I wrapped one of my friends fingers in plasters (upon reflection I wish that I would have gone more over the top with this, either covering the whole hand in plasters or even bringing in "bloody" bandages, to add more drama to the photos) and got her to contort her hand in numerous different ways. I went for some more gentle, a falling hand to represent death, and some more strained, desperate, to convey pain.

Once I had my images I took them into Photoshop to edit them digitally. I wanted to push them further, but not overwork them because I thought that the images had a lot of meaning in them already. Any further work on them had to also be relevant to the idea. I experimented with the usual cropping and grain filter to see how some iterations would compare, and then had the idea of adding an over-all pattern. When I first began working on the Index poster and was working with plasters on the scanner, I noticed that when you zoom in on the fabric it reveals a pattern. Since the images had been zoomed in on and cropped so heavily, I tried out implementing this in the designs. I worked with the dot pattern in a lot of different ways however, I decided that I didn't like any of those outcomes. The pattern reads more as polka-dots and does not fit in with the theme of the poster or look contemporary, so I scrapped it.

Having gone back to my photos and trying to think of a new way to manipulate them, I thought about how I could re-visit my research and idea and use this further. I wanted to focus on how I could convey the pain and contortion felt when dying of an infected pinprick. I decided to layer up two of the photos, to make it look like the hands were being held out in shock, I then selected jagged sections and deleted or moved them in order to achieve a sharp collage effect that contrasted with the soft gradients. Along with the high contrast between light and dark, with the brightest bits being the plasters in order to draw the focus to them, I think that this process produced the most successful outcome.

Thursday, 12 December 2019

Icon Development

Having completed and pasted up my final outcome for Symbol, I began re-working my ideas for Icon with the intention of pasting it up (due to the sizing issue with my last poster). When I was refining my ideas I settled on the X-Ray idea to represent my research involving the ingestion of safety pins. Previous crits have confirmed that this research is interesting enough to use, and I also conducted a photo-shoot using the X-Ray imagery for development which I thought was successful. I thought back to when I was producing collage at the start of the project, and how the combination of abstract shapes and gradients reminded me of organs within the body. I though that these two elements would work well together and produce some interesting collage.

I tried and tested multiple ways of producing collage with this particular imagery involved. I began by using layers - the bottom one was a print out of the X-ray, then I cut out organ shapes using my own black and white photographs and assembled them on a sheet of acetate, layering this over the first layer. I then created a third layer, another sheet of acetate, with safety pins collages onto it. I made each layer of the on a separate sheet so that I could layer them up on the scanner, however, I had trouble with this as the layers never lined up correctly. The production also wasn't brilliant, the outcomes were very dark and too grainy.

Due to the scanner not working to produce my collage, I decided to take each layer into Photoshop and assemble it digitally. This way, I could experiment with cropping and rotating really quickly, as well as inverting the images. It also was really useful to go through all the layer blend modes, this created so many different outcomes that I could then developing even further by cropping them down. I was really enjoying the outcomes that I made, I like how the element of the X-Ray is visible but it abstracted so that the focus remains on the pin/s. The abstract shapes (or 'organs') also don't read as organs, but add an element of abstract collage to the design that pushes it visually further and helps communicate the 'injected' theme.

Although I thought the outcomes were good, they didn't seem completely finalised. I considered going back to my X-Ray photo-shoot and cropping some down instead. However, before I could do so, I asked some friends for their feedback. Someone suggested that instead of using one collaged image of a bent safety pin, I should use one of my photographs from my first photo-shoot. These images still focused on abstracted safety pins, but they were a lot more minimal and refined. I took one of the best images and layered it up on top of the collage. I immediately saw an improvement in the design and was happier to call it finalised. I think that the design successfully communicates my ideas and research into the ingestion of safety pins, due to the subtle imagery and heavy shadow combination. A passer by complimented the design and pointed out immediately that 'it looks like an X-Ray' - job done.

Wednesday, 11 December 2019

Poster Pasting

As I was happy for my final design for Symbol, it was time to paste it up as a test. This was the first time that I have ever used Adobe Acrobat to tile a large poster - and as you can tell in the photos, I had some trouble with sizing. As a first time, it's not too bad, however, I wish that I could have seen this design without the distractions of the border. I hope to learn from my mistakes, and will hopefully have time to post up another one of my designs for this project. Despite these setbacks, I did still learn things from the process - I love the grainy quality. When a grain filter has been applied in Photoshop and is then printed at a larger scale it just has a sense of togetherness, as well as a contemporary feel. I also really enjoyed ripping the poster down - and this made for some really interesting adaptations to my design that I photographed.

Monday, 9 December 2019

Idea Development / Crit

After contemplating my digital collages made from my eclipse photo-shoot, I decided to go back to the original images and do some physical work with them instead. I cropped, zoomed in, and overlaid them using the scanner, however, I am not best pleased with the results. As I mentioned previously, all the meaning has been stripped away as the contrast has been upped and eclipse elements cropped out - leaving the images with only the safety pins. I think that the process is good and the texture and grit of the final images is right, but there definitely needs to be more meaning behind these images.

As I felt I was getting bogged down, I decided to re-visit the definition of Icon Index and Symbol and think about my ideas once again, after trying a couple of failed processes. Separating a smaller number of ideas (3) into the different categories was really helpful as it was a lot clearer to see. It helped me to realise that one of my earlier designs is in fact perfect for my symbol outcome. The design comes from my moon grid that was cropped to show the gradients within the circles. I feel that the process and theme alike are really strong and represent my ideas well - the design is also contemporary and I can see it being the right tone of voice for the Oripeau project.

Furthermore, I had to think about my other two posters - Index and Icon. I struggled with these two categories as I kept getting them muddled up. This was because I would take images that were suitable for Icon, then collage and abstract them so they would work for Index, however they still depicted safety pins. This left me confused. After my chat with Ben though, we had a think about the one idea I had not explored yet, Walter Hunt's death, and how this could fit in. We discussed 'the direct consequences' of a pin prick - and came up with the Index of a plaster. I thought that if I did some photography with a plaster and abstracted it in the same way I have done previously, the outcome would look really good - and the ideas would still be visually communicated.

For Icon, I really felt that my X-Ray images were almost there. I think that I want to revisit them and simply refine them. I need to look at how the x-ray can be visually communicated clearer within the frame we have been given. I also really want to get on with my stomach collage idea that I have had for so long.

- Confirmation that collage needs to be cleaned up and refined

- Definitely go ahead and collage with plaster images once I have taken them

- Confirmation of good and interesting research

- Possibly try and incorporate death more into Index or Icon?

- Go ahead with digestion

Photoshoots + Development

After my crit I conducted a photo-shoot similar to the one I did previously for this project. The images that I produced visually convey the idea that came from my research on superstition and the solar eclipse in Mexico. I used the same set up as before however in order to convey the eclipse idea I crafted a simple stencil to shine light through. The thing that I like best about these photographs is the high contrast, which creates a lot of drama. I also think that the dark, negative space creates connotations with the night sky - linking back to the eclipse. In my opinion, these photographs are refined as well as interesting - both qualities that Oripeau are looking for. However, reflecting on them I feel that they do not have the right tone of voice for the poster project. Perhaps they remind me too much of Man Ray's black and white surrealist photography? In a sense, they are too clean, polished and shiny to be a contemporary poster. I want to hopefully move away from photography and more into design, which I attempted with my digital collages:

On a whole, I was not very happy with these outcomes. They began to confuse me as they blurred the lines between Icon and Index too much - they depict safety pins and so are suited to Icon, however they are so heavily abstracted that they also suit Index. They begin to add so much drama and shadows into the images that although they depict safety pins, all meaning is lost. These images do not portray the solar eclipse in mexico. Although I enjoy the twisted metal and abstract forms, there is little to discuss when it comes to the meaning of these designs.

Before moving away from photography I used the same set up to try out some different outcomes. These images visually communicate the idea of the large amount of safety pins that are ingested. I tried to convey this my layering up an x-ray with a thin sheet of plastic to create an interesting set for the pins to sit on. In conjunction with the high contrast they make for really interesting photographs - I am thinking about possibly picking out some of my favourites, cropping the most interesting parts, and considering them as final outcomes for Icon. I like this because the pin can be shown in an interesting way - such as an x-ray or someones stomach. In my opinion this idea is visually interesting and I think that it would work well visually as an outcome. I really want to take this idea further for outcome, if I don't like the photographs as finals then I may play around with collage.

Saturday, 7 December 2019

Mike Joyce Research

Mike Joyce moved to New York City’s East Village in 1994 and was incredibly influenced by the art scene there, much like Dan Friedman. After working for several creative companies and a stint at MTV, two years later he founded Stereotype Design, a one-man studio specializing in wide-ranging projects for the entertainment industry. In the early years he created album covers and posters for indie bands that he was friends with, which eventually led to work with developing labels and, later down the line, big record companies like Sony, Capitol, Columbia and others, even Blue Note, who Reid Miles designed for in the 1950s and 60s. Mike taught at the School of Visual Arts for seven years. He lives and works in the West Village of New York City and refuses to design wedding invitations.

Music packaging is often seen as a dying sector, but opportunities continue to open up for Joyce. Sony Music Entertainment’s catalogue division, Legacy Recordings, is one new client. Legacy repackages and re-issues music, often with deluxe extras thrown in for fans who still go to the trouble of purchasing CDs or vinyl. According to Joyce, this makes for dream projects.

In 2012 Mike launched Swissted, a personal project combining his love of Swiss graphic design and punk rock by redesigning vintage punk, hardcore, new wave, and indie rock show flyersinto hundreds of vivid International Typographic Style posters. Each design is set in lowercase Berthold Akzidenz-Grotesk medium—not Helvetica.

Music packaging is often seen as a dying sector, but opportunities continue to open up for Joyce. Sony Music Entertainment’s catalogue division, Legacy Recordings, is one new client. Legacy repackages and re-issues music, often with deluxe extras thrown in for fans who still go to the trouble of purchasing CDs or vinyl. According to Joyce, this makes for dream projects.

His creative process includes listening to the album and doing a bit of research about the band and their past activities, and looking at their website. He might receive a brief from the label, or the band’s agent, but sometimes he’ll work directly with the artist.

In 2012 Mike launched Swissted, a personal project combining his love of Swiss graphic design and punk rock by redesigning vintage punk, hardcore, new wave, and indie rock show flyersinto hundreds of vivid International Typographic Style posters. Each design is set in lowercase Berthold Akzidenz-Grotesk medium—not Helvetica.

Joyce’s designs clearly are inspired by Swiss modernism, a type of design that he says he has a love for, however, certain parts of his work hold clear and obvious inspiration from Reid Miles. Yes, his Swissted project is strictly swiss design but Joyce’s ‘style’ adapts when he is designing new blue note covers or work for The Lemonheads. In a sense, he is a chameleon, and it is hard to pin down his style. It changes from client to client. It can be clean-cut in the style of Max Bill or grunge and New Wave in the style of Wolfgang Weingart or David Carson. He is extremely versatile when it comes to the world of design for music.

Dan Friedman Research

Dan Friedman was born in Ohio in 1945. After graduating from the Carnegie Institute of Technology, he attended both the Ulm School of Design and Schule für Gestaltung Basel, where he studied under Wolfgang Weingart and Armin Hofmann. Here, he clearly picked up the country’s hallmark emphasis on the grid and meticulous typography. In 1969 he moved back to the United States and had a very successful and interesting career before his untimely death from AIDS in 1995. He was one of the first employees at the huge design studio Pentagram and also has a large presence in the New York East Village scene in the 1980s. Friedman’s own work became more experimental, often veering into the world of sculpture and furniture design.

In the ’70s he was the epitome of success in his field, with teaching posts at Yale and positions at Anspach Grossman Portugal and Pentagram. But in 1982, deeply disenchanted, he restarted his private practice. “What I realized in the 1970s, when I was doing major corporate identity projects, is that design had become a preoccupation with what things look like rather than with what they mean.” His work always strived, taught and was, ultimately, deeply communicative. His work in the 1990s was a continuation of what he had always done, but building in momentum and speed.

Friedman was chosen as an AIGA medalist for his eccentric and revolutionary philosophy of “Radical Modernism”—a blend of Modernism archetypes and postmodern energy. Active in the realms of education, design, art, writing, and social activism, Friedman’s body of work prompted a distinct displacement of modernist design, incorporating more emotion and energy into Modernist ideals.

“I have, for many years, used my home to push modernist principles of structure and coherency to their wildest extreme, I create elegant mutations radiating with intense color and complexity in a world that is deconstructed into a goofy, ritualistic playground for daily life.”

In 1994, near the end of his life, Friedman offered this 12 point ‘radical modernist’ agenda for life and work:

- Try to express personal, spiritual, and domestic values even if our culture continues to be dominated by corporate, marketing, and institutionalised values.

- Choose to remain progressive; don’t be regressive. Find comfort in the past only if it expands insight into the future and not just the sake of nostalgia.

- Embrace the richness of all cultures; be inclusive instead of exclusive.

- Think of your work as a significant element in the context of a more important, transcendental purpose.

- Use your work to become advocates of projects for the public good.

- Attempt to become a cultural provocateur; be a leader rather than a follower

- Engage in self restraint; except the challenge of working with reduced expectations and diminished resources.

- Avoid getting stuck in corners, such as being a servant to increasing overhead, careerism, or narrow points of view.

- Bridge the boundaries that separate us from other creative professions and unexpected possibilities.

- Use the new technologies, but don’t be seduced into thinking that they provide answers to fundamental questions.

- Be radical.

Wolfgang Weingart Research

Born in Germany in 1941, Wolfgang Weingart is the father of New Wave Typography (or Swiss Punk Typography). In 1958 Weingart enrolled at the Merz Academy in Stuttgart where he studied graphic arts and developed skills in linocut, woodblock printing and typesetting. His first design job was a three-year apprentiship at Ruwe Printing, where he learned typesetting in hot metal hand composition. Weingart says his time here still has a big influence on the work he produces today. Here he met Emil Ruder and Armin Hoffman, and relocated with them to Basel in 1963 where he attended the Basel School of Design.

In 1968, he was requested to teach typography at the institution’s newly established department Weiterbildungsklasse für Grafik and went on to accept a teaching position at the Yale Summer Program in Graphic Design in Brissago, Switzerland, upon Armin Hofmann’s request. “I went to Basle because of Emil Ruder and Armin Hofmann, but I was quickly disappointed. Hofmann went off on a one-year sabbatical, and I had the feeling I wasn’t learning anything with Ruder.”

For over four decades Weingart has extensively taught and delivered lectures across Europe, Asia, New Zealand, North and South America, and Australia. According to him, he never influenced his students to adopt a certain type of style, especially his own. However, his students misunderstood his teaching as his own style and spread it around as ‘Weingart style’. According to Weingart, "I took 'Swiss Typography' as my starting point, but then I blew it apart, never forcing any style upon my students. I never intended to create a 'style'. It just happened that the students picked up—and misinterpreted—a so-called 'Weingart style' and spread it around."

In 1968, he was requested to teach typography at the institution’s newly established department Weiterbildungsklasse für Grafik and went on to accept a teaching position at the Yale Summer Program in Graphic Design in Brissago, Switzerland, upon Armin Hofmann’s request. “I went to Basle because of Emil Ruder and Armin Hofmann, but I was quickly disappointed. Hofmann went off on a one-year sabbatical, and I had the feeling I wasn’t learning anything with Ruder.”

For over four decades Weingart has extensively taught and delivered lectures across Europe, Asia, New Zealand, North and South America, and Australia. According to him, he never influenced his students to adopt a certain type of style, especially his own. However, his students misunderstood his teaching as his own style and spread it around as ‘Weingart style’. According to Weingart, "I took 'Swiss Typography' as my starting point, but then I blew it apart, never forcing any style upon my students. I never intended to create a 'style'. It just happened that the students picked up—and misinterpreted—a so-called 'Weingart style' and spread it around."

From 1978 to 1999, Wolfgang Weingart served as the member of the Alliance Graphique Internationale, A group that Max Huber was also a part of in 1958. Weingart also contributed to the the editorial board of the magazine, Typographische Monatsblätter, for eighteen long years, A publication that Dan Friedman and Emil Ruder also contributed to.

“In my opinion, most designers don’t think or develop anything for themselves any more. They just process fragments. The result is emotional chaos. Today students look to Emigre magazine for ideas. They find this chaos wildly attractive: they imitate it and think it’s modern.”

Weingart taught a new approach to typography that influenced the development of New Wave, Deconstruction and much of graphic design in the 1990s. While he would contest that what he taught was also Swiss Typography, since it developed naturally out of Switzerland, the style of typography that came from his students led to a new generation of designers that approached most design in an entirely different manner than traditional Swiss typography.

Weingart is known to have a rebellious mind-set and has liked to push the limits of what is considered as ‘the norm’ and from an early stage he broke the typographic rules by freeing letters from their restricting design grids. He spaced them, underlined them or reshaped them and reorganized type-setting. Weingart believed that the development of the Swiss Typography was becoming stagnant as it was sterile and anonymous, as Swiss style emphasizes on being neat and eye-catching, and on its readability and objectivity. It is also identified for its immense simplicity and exhortation to beauty and purpose. These two principles are achieved by using asymmetric layouts, grids, sans-serif typefaces, left-flushes and simple but effective photography. These elements are produced in a simple but highly logical, structured, stiff and harmonious manner.

His goal was to breathe new life into the teaching of new typography. He believed that the only way to break typographic rules was to know them; an advantage he gained from his apprenticeship.

Friday, 6 December 2019

Max Bill Research

Max Bill was born in Switzerland on the 22nd of December in 1908. After becoming a silversmith apprentice, like many great Swiss designers, Bill studied at the Bauhaus school. He studied there from 1927 to 1929 under great artists and designers such as Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee and Oskar Schlemmer. After his studies at the Bauhaus, Bill moved to Zurich, this is also where Max Huber’s career began.

Bill is certainly seen as having a huge impact on Swiss design due to his theoretical writing and progessive work. His work always exuded a sense of clarity and precise proportions - and as well as this, his connections to the days of the Modern Movement gave him a certain authority in the design world. (Modernism at this time was incredibly impactful on Swiss design, and inspired many designers work including Max Huber’s).

Bill was not only a very talented designer, but also an architect, artist, and industrial designer. He worked with many mediums over a range of practices. From designing and building his own home and studio (a superb, stripped-down building which would later influence Brutalist architects), to elegant clocks and watches designed for Junghans, a long-term client. As a designer and artist, Bill sought to create forms which visually represent the New Physics of the early 20th century. He sought to create objects so that the new science of form could be understood by the senses: that is as a concrete art. His idea of Concrete Art was that it should be purely abstract. “A work of art,” he wrote, “must be entirely conceived and shaped by the mind before its execution. It shall not receive anything of nature’s or sensuality’s or sentimentality’s formal data. We want to exclude lyricism, drama, symbolism, and so on.”

Despite his vast array of talents, Bill remained ubiquitous in the art world. He designed memorable posters for the Munich Olympics in 1972; he influenced a generation of Op Artists; and his sculptural works, many of them based on a Möbius strip or an endless ribbon, popped up in plazas throughout Switzerland and Germany. All of these works were striking and colourful.

Bill is certainly seen as having a huge impact on Swiss design due to his theoretical writing and progessive work. His work always exuded a sense of clarity and precise proportions - and as well as this, his connections to the days of the Modern Movement gave him a certain authority in the design world. (Modernism at this time was incredibly impactful on Swiss design, and inspired many designers work including Max Huber’s).

Bill was not only a very talented designer, but also an architect, artist, and industrial designer. He worked with many mediums over a range of practices. From designing and building his own home and studio (a superb, stripped-down building which would later influence Brutalist architects), to elegant clocks and watches designed for Junghans, a long-term client. As a designer and artist, Bill sought to create forms which visually represent the New Physics of the early 20th century. He sought to create objects so that the new science of form could be understood by the senses: that is as a concrete art. His idea of Concrete Art was that it should be purely abstract. “A work of art,” he wrote, “must be entirely conceived and shaped by the mind before its execution. It shall not receive anything of nature’s or sensuality’s or sentimentality’s formal data. We want to exclude lyricism, drama, symbolism, and so on.”

In 1937 Bill formed the group Allianz in Switzerland with a number of other artists, including Max Huber. The Allianz group advocated the concrete art theories of Bill with more emphasis on color than their Constructivist counterparts.

Despite his vast array of talents, Bill remained ubiquitous in the art world. He designed memorable posters for the Munich Olympics in 1972; he influenced a generation of Op Artists; and his sculptural works, many of them based on a Möbius strip or an endless ribbon, popped up in plazas throughout Switzerland and Germany. All of these works were striking and colourful.

Thursday, 5 December 2019

Max Huber Research

Max Huber was born in Switzerland on the 5th of June 1919. His career began in 1935 in Zurich, where he worked for an advertising agency. Prior to this, however, at the age of 17 Huber registered to the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts. Here he was taught by great Swiss designers: Ernst Gubler, Gottlieb Wehrli, Heinri MŸller, Walter Roshardt, Otto Weber and Alfred Willimann. Williman suggested Huber should spend time in the school library, where he could discover the experiments of Bauhaus-designers such as Tschichold as well as European abstract artists and russian constructivists. Huber’s design was incredibly influenced by this reading. Art and design in Zurich was buzzing with life during this time period due to German graphic artists settling in Switzerland because of the Nationalist seizure of power. It was the mixture of these Germans and several young Swiss designers that resulted in the melting pot that was: The Swiss School of Graphic Design. The practices taught resemble what we know Swiss design to be today: typographic grid systems, left-hand margin settings contrasting with a ragged right hand, sans serif typefaces, and a commitment to a clear, rational aesthetic.

At the start of WW2, Huber moved to Milan to avoid being drafted by the Swiss army. It was here that his Zurich education came in handy as he joined Studio Boggeri - one of the most important and influential graphic design studios in the world that brought Italian and Swiss design together in a beautiful combination. When Huber left his calling card at Antonio Boggari’s studio - upon the first look it appeared to be well printed. However, on further inspection the card was delicately hand written with perfect penmanship and careful spacing. Boggari hired Huber immediately, despite him knowing virtually no Italian. Milan design was a melting pot of illustration, painting, photography, and printing.

Huber created his best work in Milan, however, when Italy entered the war in 1941, he was forced to move back to Switzerland where he began a collaboration with Werner Bischof and Emil Schultness for the influential art magazine Du. It was also here between 1942 and 1944 he spent time with the members of the Alliance Association of Modern Swiss Artists in Zurich, a group of modern Swiss artists led by Max Bill - and worked closely alongside Reid Miles. But after the war, Huber was drawn back to Milan and immigrated there permanently. Huber believed that in the aftermath of war, design had the capacity to restore human values.

At the start of WW2, Huber moved to Milan to avoid being drafted by the Swiss army. It was here that his Zurich education came in handy as he joined Studio Boggeri - one of the most important and influential graphic design studios in the world that brought Italian and Swiss design together in a beautiful combination. When Huber left his calling card at Antonio Boggari’s studio - upon the first look it appeared to be well printed. However, on further inspection the card was delicately hand written with perfect penmanship and careful spacing. Boggari hired Huber immediately, despite him knowing virtually no Italian. Milan design was a melting pot of illustration, painting, photography, and printing.

Huber created his best work in Milan, however, when Italy entered the war in 1941, he was forced to move back to Switzerland where he began a collaboration with Werner Bischof and Emil Schultness for the influential art magazine Du. It was also here between 1942 and 1944 he spent time with the members of the Alliance Association of Modern Swiss Artists in Zurich, a group of modern Swiss artists led by Max Bill - and worked closely alongside Reid Miles. But after the war, Huber was drawn back to Milan and immigrated there permanently. Huber believed that in the aftermath of war, design had the capacity to restore human values.

"He was a splendid mix; he had irrepressible natural talent and a faultless drawing hand; he possessed the lively candour of the eternal child; he was a true product of the Swiss School; he loved innovatory research; he boasted a lively curiosity, being quick to latch on - not without irony - to the most unpredictable ideas, and he worked with the serious precision of the first-rate professional."

- Giampiero Bosoni

He never used his images in a strict sense. He often mixed unframed flat photographic and typographic elements with strips of colour to convey a certain feeling of dynamism and speed, in the same way that Reid miles conveyed Jazz so well in his album covers. He used recognizable elements in his design, without having them tell a story. His work concentrated on photographic experiments and clear type combined with the use of bold shapes and primary colors. His strict grids were easily identifiable. Huber favoured clarity, rhythm and synthesis. He used succinct texts, composed from different hierarchical groups; a large title with secondary information in a smaller type, a sequence of levels. Again, similarly to Miles, Huber’s work favours Modernism.

When looking back on Huber’s influences you see a lot of personal and professional friendships. He was inspired by other designers that he met, possibly even Reid Miles. I like to think so, as I feel such a connection between both when looking at their designs. One of the freelance jobs he executed with great enthusiasm was the design of record covers, posters and publications for jazz events. He was fond of jazz-music and linked it to his own design by bringing the rhythm into his visuals. The music was represented through the relationship between signs and colours.

Reid Miles Research

Miles was born in Chicago on July 4th 1987, but following the stock market crash his mother moved with him to California in 1929 - this is where Miles grew up. After high school Miles joined the Navy and, following his discharge, moved to Los Angeles to enroll at Chouinard Art Institute.

According to Miles himself, he didn’t enrol because of some lofty ambitions towards art. He told in a series of interviews that he did it because of a girl who he was dating at the time. Miles had also just returned from World War II and could use the G.I. Bill education benefits. To him, it felt like a better idea to go to an easy art school than anywhere else.

After graduating Miles moved to New York looking for work as a designer. He was given his first job by artist and graphic designer John Hermansader - who produced work for Blue Note Records along with Paul Bacon prior to hiring Miles. Miles is heavily credited for Blue Note’s design identity, however, Hermansader and Bacon were the ones who developed the groundwork for the design style. Miles was the one to add his own twist - causing the designs to become extremely popular as they gained a certain flare that was not present when in the hands of the two former men.

According to Miles himself, he didn’t enrol because of some lofty ambitions towards art. He told in a series of interviews that he did it because of a girl who he was dating at the time. Miles had also just returned from World War II and could use the G.I. Bill education benefits. To him, it felt like a better idea to go to an easy art school than anywhere else.

After graduating Miles moved to New York looking for work as a designer. He was given his first job by artist and graphic designer John Hermansader - who produced work for Blue Note Records along with Paul Bacon prior to hiring Miles. Miles is heavily credited for Blue Note’s design identity, however, Hermansader and Bacon were the ones who developed the groundwork for the design style. Miles was the one to add his own twist - causing the designs to become extremely popular as they gained a certain flare that was not present when in the hands of the two former men.

In late 1955, when Miles was hired for Blue Note, the records changed to a 12” format. It was Miles’ job to redesign the covers for all existing cover art. He began with what would become his most famous cover - Milt Jackson and The Thelonious Monk Quintet. He designed 500 covers over a period of 15 years and was paid $50 a cover.

Miles was an eccentric character, even in terms of his death. He died in interesting circumstances. A stranger had parked on his private studio driveway and he proceeded to use his own car to push the car off, and then got it towed. The stranger took Miles to court, and Miles won the case. Following the trial, when Miles and the stranger we’re leaving, Miles hurled abuse at the man and his heart gave out. His body apparently tumbled down the entrance steps of the court. He requested in his will to have his ashes spread at MacArthur Park, however, so many ashes were being spread there at that time that it was creating a health hazard. Miles’ Ashes sit in a small metal box on the mantle-piece in his studio, on which there is a button. When the button is pressed, a small speaker inside hurls insults at whoever pressed it.

During the Fifties, Miles pushed forward the way the typography is treated with his bold, playful designs, creative use of typefaces, and his distinct preference for contrast and asymmetry. His way of deconstructing and expanded type was new and innovative. The graphic elements that he used the majority of the time were simple blocks and lines that had effective results. As well as this the colours that he used most often were white, black, red and blue. His designs scream modernism. The way he played with type in such a fresh way that was previously sparse - stacking and cropping. His layouts seem to be so perfected that to lay the elements any other way would be wrong.

One of the most important things that I learnt from Miles (as well as the modernist movement as a whole) is an idea of how to convey a single message or idea in a powerful and simple way. The design just carries the message, rather than attempt to be the message. His designs have simple elements, they’re relatively simple. However, they are a fine example of how knowing which screw to turn is how designers can charge what they do.

Looking at Miles’ work is like looking at jazz realised. A printed visualisation. Even to someone who has never heard jazz - Miles’ covers look like what jazz covers should look like.

One of the most surprising, or possibly unsurprising, things about Miles was that he was not a fan off jazz. A lot of designers have said that his disconnection from the genre is what helped him create such spot on design. “it is interesting to see that a designer who really managed to capture the essence of his time, was also, in a way, disconnected from that very essence … it is perhaps ‘distance’ not engagement that makes the designer.”

One of the most important things that I learnt from Miles (as well as the modernist movement as a whole) is an idea of how to convey a single message or idea in a powerful and simple way. The design just carries the message, rather than attempt to be the message. His designs have simple elements, they’re relatively simple. However, they are a fine example of how knowing which screw to turn is how designers can charge what they do.

Monday, 2 December 2019

Crit + Idea Refinement

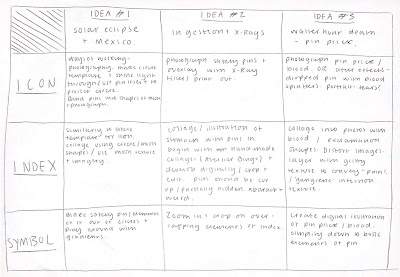

Today, I also planned out what I was going to do next by organising my ideas into a chart. This way, I can visualise what goes where in terms of Icon, Index and Symbol. This might be slightly over-kill, however, It has helped me manage to pick my three best ideas and how I can use them for each category. I am going to begin with photography for icon and whichever is best, finalise that. Then, with the two that are left, move onto Index. Again, which ever is best, I will finalise. And then, I will develop the last idea into a symbol.

Sunday, 1 December 2019

6 Degrees of Seperation

Reid Miles

https://viljamis.com/2015/the-iconic-work-of-reid-miles/Born in Chicago, 1927

Hired by Francis Wolff of Blue Note around 1955 to design album covers

Best known and celebrated for his Blue Note designs in the 1950s and 1960s

Max Huber

https://www.domusweb.it/en/design/2010/02/16/max-huber-maxieland-jazz-.htmlBorn in Switzerland, 1919

Began his career in 1936

Celebrated for his jazz covers, posters and magazines

Encyclopedia of Jazz cover Messaggerie Musicali, 1952

Between 1942 and 1944 he spent time with the members of the Alliance Association of Modern Swiss Artists in Zurich, a group of modern Swiss artists led by Max Bill formed in 1937

Max Bill

https://www.bauhaus100.com/the-bauhaus/people/students/max-bill/Born in Switzerland, 1908

An artist, architect, industrial designer, graphic designer, and teacher

Studied at the Bauhaus School before forming Alliance Association of Modern Swiss Artists

widely considered the single most decisive influence on Swiss graphic design beginning in the 1950s

Wolfgang Weingart

https://www.typographicposters.com/wolfgang-weingart

Born in 1941 in Germany near the Swiss border of Germany

The father of New Wave Design / Swiss Punk Typography - a break or natural progression of the Swiss Style. Sans-serif font still predominates, but the New Wave differs from its predecessor by stretching the limits of legibility.

Born in 1941 in Germany near the Swiss border of Germany

The father of New Wave Design / Swiss Punk Typography - a break or natural progression of the Swiss Style. Sans-serif font still predominates, but the New Wave differs from its predecessor by stretching the limits of legibility.

Dan Friedman

https://thenewwavetype.wordpress.com/tag/new-wave-typography/Born in Cleveland, 1945

Dan Friedman was a student under Wolfgang Weingart whilst Weingart taught in United States of America.

He often referred to himself as a radical modernist to differentiate himself from the constraints of Modernism and the post-modern label.

He is a contributor to the journal Typographische Monatsblätter, for which he designed a series of covers.

Mike Joyce

Mike Joyce moved to New York City’s East Village in 1994 and was incredibly influenced by the art scene thereIn 2012 Mike launched Swissted, a personal project combining his love of Swiss graphic design and punk rock by redesigning vintage punk, hardcore, new wave, and indie rock show flyers into hundreds of vivid International Typographic Style posters.

He founded Stereotype Design, a one-man studio specialising in album covers which eventually led to work with developing labels and, later down the line, big record companies like Sony, Capitol, Columbia and others, even Blue Note.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

Module Evaluation

This module has been really positive for me. I'm so glad that I chose the issue that I did, because I felt passionate and motivated the ...

-

I resized my InDesign pages to he correct size and did a small print run of a couple of pages to identify any issues. The main one being ver...

-

- Attempting to continue with current theme by developing a anthropomorphised fruit character - This was interesting in theory...